Austerity has hit local government very hard, and the biggest losses of funding have come in deprived areas[i]. This reduces resources which support community living, social support and contact for groups at particular risk of being lonely and isolated, such as young families and older people[ii]. People living in deprived communities are on average more socially isolated[iii], as well as being more significantly affected by cuts to free communal and cultural resources[iv]. Deprived communities have been disproportionately affected by government cuts[v].

The costs to mental health

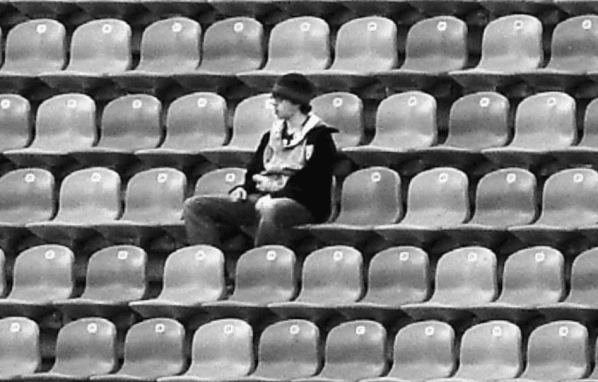

Isolation, both social and cultural[vi], is known to both precipitate mental health health difficulties, and inhibit recovery[vii]. Loneliness has a comparable mortality risk to smoking and drinking alcohol, and is a higher risk for mortality than obesity[viii]. Britain already has one of the highest levels of loneliness in Europe[ix]. Policies which increase isolation and loneliness therefore have a direct risk of damaging mental health outcomes in both the short and long term.

Isolation, both social and cultural[vi], is known to both precipitate mental health health difficulties, and inhibit recovery[vii]. Loneliness has a comparable mortality risk to smoking and drinking alcohol, and is a higher risk for mortality than obesity[viii]. Britain already has one of the highest levels of loneliness in Europe[ix]. Policies which increase isolation and loneliness therefore have a direct risk of damaging mental health outcomes in both the short and long term.

Case study: Sure start centres

More than 400 Sure Start centres closed during the first two years of the Coalition government, following a cut of one third in funding[x]. Mothers of young children are a group at high risk for developing mental health problems, with one in ten women experiencing mental health problems during or after pregnancy. Poor mothers are four times more likely to develop post-natal depression than those in the highest income bracket[xi]. Supportive social networks, including those developed at children’s centres, have been shown to decrease the level of depression experienced by this group[xii]. Early years environments are known to be critical for children’s long term development and adult mental health. Experiencing depression after birth is linked to reduced quality in mother-child interactions and child-stranger interactions[xiii]. Supporting parents to provide good early years in environments is incredibly important[xiv].

More than 400 Sure Start centres closed during the first two years of the Coalition government, following a cut of one third in funding[x]. Mothers of young children are a group at high risk for developing mental health problems, with one in ten women experiencing mental health problems during or after pregnancy. Poor mothers are four times more likely to develop post-natal depression than those in the highest income bracket[xi]. Supportive social networks, including those developed at children’s centres, have been shown to decrease the level of depression experienced by this group[xii]. Early years environments are known to be critical for children’s long term development and adult mental health. Experiencing depression after birth is linked to reduced quality in mother-child interactions and child-stranger interactions[xiii]. Supporting parents to provide good early years in environments is incredibly important[xiv].

Case study : Older people and social care

While those over 65 have overall been relatively protected from austerity[xv], the cuts to local government have meant cuts to services for older people at particular risk of loneliness. The Supporting People budget has been cut, and support staff have been removed from people living independently[xvi]. Widespread call cramming, meaning shortened visits to disabled and older people, has been reported. Older people are already more likely to be lonely[xvii], so removing or cutting lifelines of social contact is highly damaging. Concentration of social care on only the most severe need is a short termist strategy that creates problems in the long run. Those affected by the first wave of cuts are often those who only need minimal support. Without this support they are likely to suffer more and to develop more serious levels of need.

While those over 65 have overall been relatively protected from austerity[xv], the cuts to local government have meant cuts to services for older people at particular risk of loneliness. The Supporting People budget has been cut, and support staff have been removed from people living independently[xvi]. Widespread call cramming, meaning shortened visits to disabled and older people, has been reported. Older people are already more likely to be lonely[xvii], so removing or cutting lifelines of social contact is highly damaging. Concentration of social care on only the most severe need is a short termist strategy that creates problems in the long run. Those affected by the first wave of cuts are often those who only need minimal support. Without this support they are likely to suffer more and to develop more serious levels of need.

References

[i] Hastings, A., Bailey, N., Besemer, K., Bramley, G. Gannon, M., Watkins, D. (2013). Coping with the cuts? Local government and poorer communities. Glasgow: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

[ii] Hastings, A., Bailey, N., Besemer, K., Bramley, G. Gannon, M., Watkins, D. (2013). Coping with the cuts? Local government and poorer communities. Glasgow: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

[iii] Ross, C. E., Mirowsky, J., & Pribesh, S. (2001). Powerlessness and the amplification of threat: neighbourhood disadvantage, disorder and mistrust. American Sociological Review, 66, 568-591.

[iv] Hastings, A., Bailey, N., Besemer, K., Bramley, G. Gannon, M., Watkins, D. (2013). Coping with the cuts? Local government and poorer communities. Glasgow: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

[v] Berry, C., While, L. (2014). No. 6 – Local authority spending cuts and the 2014 English local elections. Sheffield: SPERI.

[vi] Bhugra, D., Arya, P. (2005). Ethnic density, cultural congruity and mental illness in migrants, International Review of Psychiatry, 17, 2, 133-137.

[vii] Warner, R. (2000). The environment of schizophrenia: Innovations in policy, practice and communications. London: Brunner-Routledge.

[viii] Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. Plos, Medicine.

[ix] ONS. (2014). Measuring National Wellbeing: European Comparisons, 2014. London: ONS

[x] 4Children. (2012). Sure Start Children’s Centres Census 2012. London: 4Children.

[xi]Marmot, M. (2010). Fair society healthy lives. London: The Marmot Review.

[xii] Colletta, W.D. (1983). At risk for depression: A study of young mothers, The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development, 142, 2, 301-310.

[xiii] Stein, A., Gath, D.H., Bucher, J., Bond, A., Day, A., Cooper, P. J. (1991). The relationship between post-natal depression and mother-child interaction, British Journal of Psychiatry, 158,46-52.

[xiv]Marmot, M. (2010). Fair society healthy lives. London: The Marmot Review.

[xv] Lipton, R. (2015). The Coalition’s Social Policy Record: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015, Research Report 4, Social Policy in a Cold Climate, Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

[xvi] Hastings, A., Bailey, N., Besemer, K., Bramley, G. Gannon, M., Watkins, D. (2013). Coping with the cuts? Local government and poorer communities. Glasgow: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

[xvii] Cattan, M., White, M., Bond, J., Learmouth, A. (2005). Preventing social isolation and loneliness among older people: a systematic review of health promotion interventions, Ageing and Society, 25, 1, 41-67.

[i] Hastings, A., Bailey, N., Besemer, K., Bramley, G. Gannon, M., Watkins, D. (2013). Coping with the cuts? Local government and poorer communities. Glasgow: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

[ii] Hastings, A., Bailey, N., Besemer, K., Bramley, G. Gannon, M., Watkins, D. (2013). Coping with the cuts? Local government and poorer communities. Glasgow: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

[iii] Ross, C. E., Mirowsky, J., & Pribesh, S. (2001). Powerlessness and the amplification of threat: neighbourhood disadvantage, disorder and mistrust. American Sociological Review, 66, 568-591.

[iv] Hastings, A., Bailey, N., Besemer, K., Bramley, G. Gannon, M., Watkins, D. (2013). Coping with the cuts? Local government and poorer communities. Glasgow: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

[v] Berry, C., While, L. (2014). No. 6 – Local authority spending cuts and the 2014 English local elections. Sheffield: SPERI.

[vi] Bhugra, D., Arya, P. (2005). Ethnic density, cultural congruity and mental illness in migrants, International Review of Psychiatry, 17, 2, 133-137.

[vii] Warner, R. (2000). The environment of schizophrenia: Innovations in policy, practice and communications. London: Brunner-Routledge.

[viii] Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. Plos, Medicine.

[ix] ONS. (2014). Measuring National Wellbeing: European Comparisons, 2014. London: ONS

[x] 4Children. (2012). Sure Start Children’s Centres Census 2012. London: 4Children.

[xi]Marmot, M. (2010). Fair society healthy lives. London: The Marmot Review.

[xii] Colletta, W.D. (1983). At risk for depression: A study of young mothers, The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development, 142, 2, 301-310.

[xiii] Stein, A., Gath, D.H., Bucher, J., Bond, A., Day, A., Cooper, P. J. (1991). The relationship between post-natal depression and mother-child interaction, British Journal of Psychiatry, 158,46-52.

[xiv]Marmot, M. (2010). Fair society healthy lives. London: The Marmot Review.

[xv] Lipton, R. (2015). The Coalition’s Social Policy Record: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015, Research Report 4, Social Policy in a Cold Climate, Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

[xvi] Hastings, A., Bailey, N., Besemer, K., Bramley, G. Gannon, M., Watkins, D. (2013). Coping with the cuts? Local government and poorer communities. Glasgow: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

[xvii] Cattan, M., White, M., Bond, J., Learmouth, A. (2005). Preventing social isolation and loneliness among older people: a systematic review of health promotion interventions, Ageing and Society, 25, 1, 41-67.