|

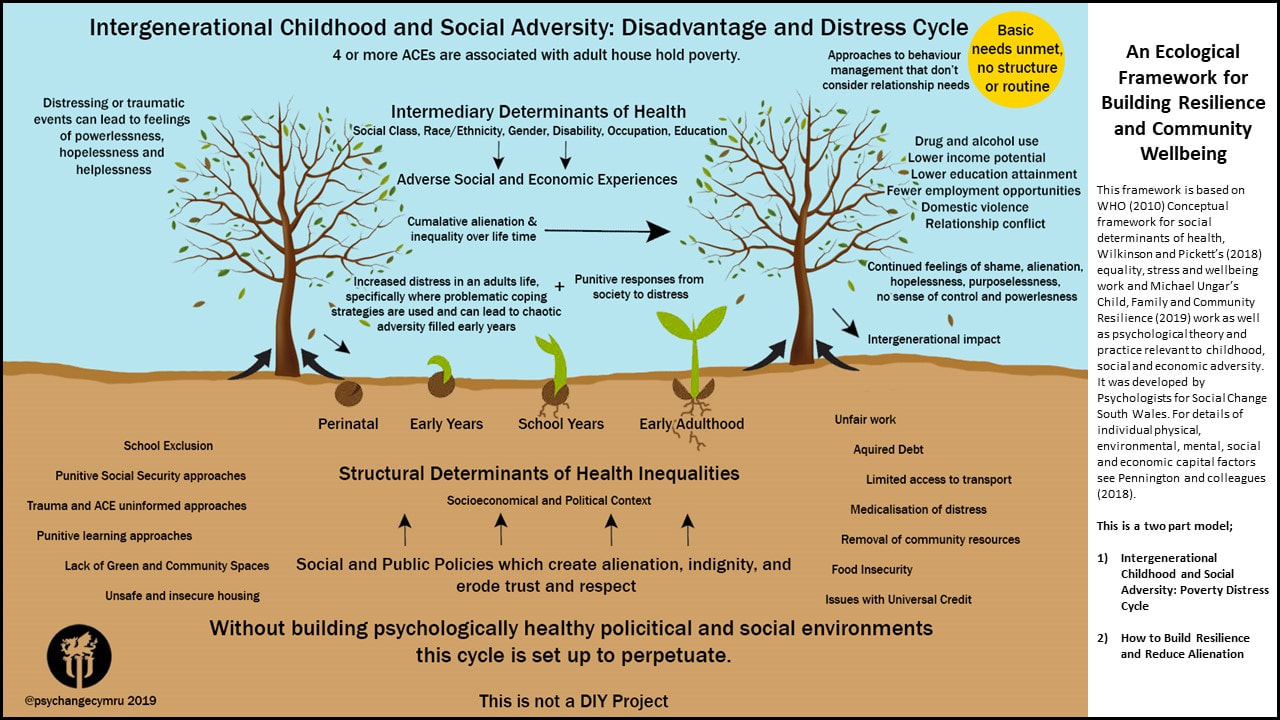

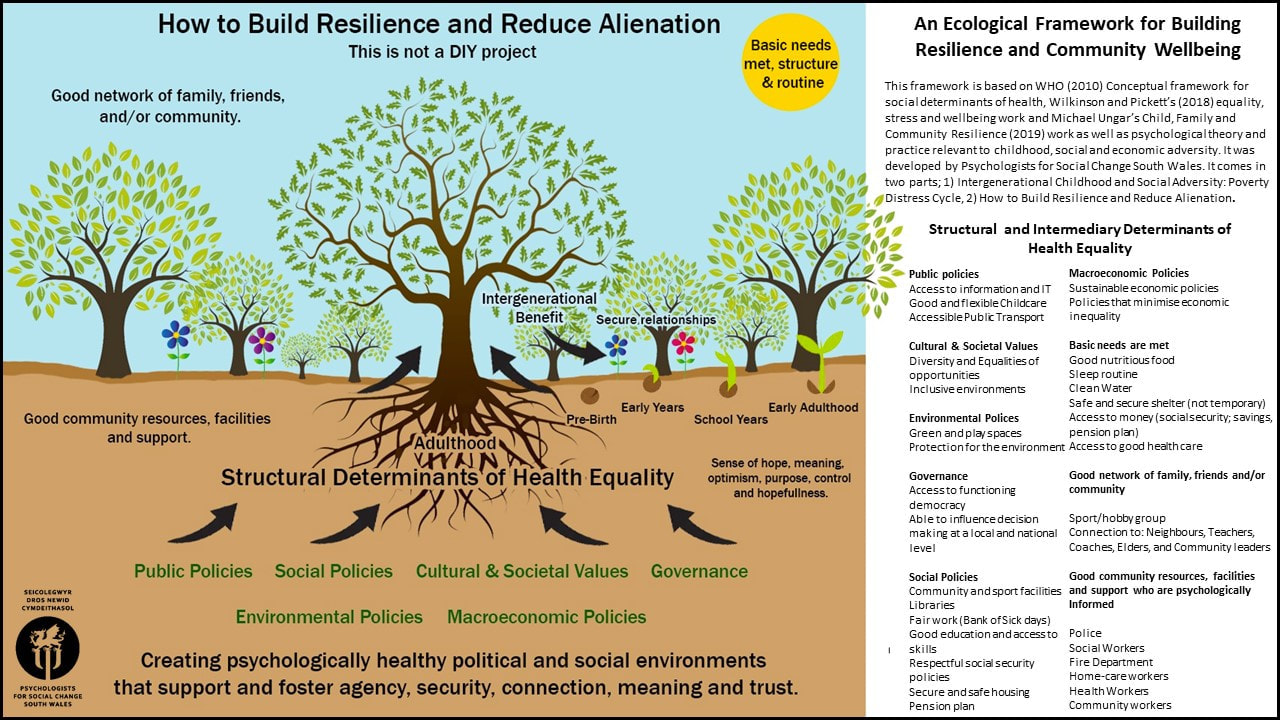

South Wales PSC are on the case to make sure the Welsh government’s approach to mental health is focused on creating mentally healthy communities so that everyone can thrive Photo by David Chubb on Unsplash My name is Lyndsey and I was born in 1988 to a Welsh mother and father. My father left when I was two and my mum raised me and my two older brothers alone. Mum worked really long hours to provide for us the best she could, but with three children and a house to run, she struggled. Both financially and mentally.I was brought up on a well-known housing estate in south Wales. As a young child, it was a scary place to be. Emergency services were always around because of burnt-out cars, always gang trouble and issues with drugs. As I got older, I became oblivious to the trouble and found the community spirit amazing. Everyone would help each other out with anything needed. I enjoyed primary school for a time but I experienced personal trauma and school then became a struggle for me. I never felt like I belonged there, like I was different. I used to “act out” because I never had the confidence to speak out. Going to secondary school, I no longer had the escape I needed. I struggled with my anger and felt I had nobody to turn to. I channelled my frustrations in the wrong way, which resulted in me being excluded from school with no qualifications at 15. I struggled for the next few years. I started full time work at 19. It was there I met my now husband. Things happened quickly and I fell pregnant. Once the baby arrived, I moved areas to be a family. I moved to Abertillery and struggled with the different way of life. I also had postnatal depression and had no knowledge of any support networks that could help. Being so far from my family’s help, I felt isolated and couldn’t see a way out. My mental health took a beating and I struggled to be a parent. I’ve continued to struggle, but it took my son being born in 2017 to finally get help. After battling postnatal again, my health visitor put us in touch with Families First. The help and support we’ve received from them has been phenomenal. Without the support of everyone involved at Families First, I genuinely fear my children wouldn’t have had a mother. Having them on hand has been a brilliant opportunity for me. I’ve done Circle of Security with them and that has given me the tools I need to be a better parent. They also got me onto a childcare course to give me a chance to better myself. It’s something I always wanted to do but never had the financial means. Due to my husband starting his own business, we are not entitled to any benefits. We only receive child tax credits, which means that once the bills are paid there’s barely enough money left to feed the children. We get by on £100 a week. That’s £100 to pay the mortgage, utility bills, feed and clothe our children. *** When you read a story like Lyndsey’s, it is not hard to see the connection between her life circumstances and the psychological distress she describes. Yet when it comes to doing something about people’s distress and the rising rates of mental health problems, politicians are often reluctant to acknowledge the interplay between the two. The connection to poverty is a particularly thorny issue as this would require admitting that far greater change is needed than simply employing more therapists or recruiting mental health support workers to work in schools. It would also mean bearing some culpability for the austerity policies that have led to greater levels of poverty and increased mental distress. In some ways, the Welsh government is more progressive in this regard than the UK government. We, at PSC South Wales, welcome their continued efforts lobbying Westminster to reconsider their damaging austerity and welfare reform policies, as well as their commitment to provide more support to lift people out of poverty and improve people’s wellbeing. In the ‘Prosperity for All’ report, published in 2017, Mental Health was named one of five priority areas as part of the Welsh government’s drive to improve prosperity and wellbeing (the others were Early Years, Housing, Social Care, Mental Health, Skills and Employability, with Decarbonisation added later). While we recognise the ambitious work the Welsh government is doing towards improving wellbeing, at PSC, we want to ensure that the concepts of mental health and wellbeing are not being disconnected from the bigger societal picture. Earlier this year, PSC South Wales sent the Welsh government a letter outlining some of the evidence connecting the two. We drew their attention to the fact that there was a 35-fold increase in the number of children in the UK that are classified as disabled by mental health difficulties between 1987 and 2007. We think this rise has occurred for two reasons; a rise in inequality and austerity-led increased levels of poverty. Research into adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) demonstrates that the trauma associated with the combination of ACEs and poverty makes it more likely for children to experience deeper and more prolonged levels of poverty throughout their lives and on into future generations. Approximately 40% of our health outcomes are connected to the quality of our housing, the quality and security of our employment, the quality of our social relationships as well as our education, transportation options and socioeconomic status. Those from the lowest 20% of household incomes are three times more likely to have common mental health problems and nine times as likely to receive a diagnosis of a ‘psychotic disorder’. But when presented like this, the hard stats can leave you cold. So, we made some diagrams to show the impact of how social adversity in childhood can lead to a cycle of poverty and distress, but also how things could change if the environment fostered a sense of agency, connection, meaning and trust. Our aim was to show visually that psychological wellbeing is not a DIY project. There are so many factors that play a role, many of which require political and social change for people and communities to flourish. Although we recognise the tree metaphor is limited by it connotations of hierarchy, dualist categories and binary choices (a rhizome is more appropriate, but ginger is harder to draw), its origins are based in Zimbabwean folklore and it’s used often in narrative therapy to help people recognise their strengths and resources in order to reposition blame and personal failure. Narrative therapy is based on the idea that problems are manufactured and/or maintained in social, cultural or political contexts. We therefore thought it was a good place to start to lay out our ideas from. Finally, we included Lyndsey’s story in our letter. Lyndsey kindly gave her story after co-facilitating a parents’ social action group with a psychologist from the Blaenau Gwent Families First Programme (FFP). Families First is a Welsh government-funded programme that provides help and support to families. It aims to provide families the right help at the right time before situations get worse. If statistics, diagrams and a slogan (Mental Health is not a DIY project) weren’t enough , her life story powerfully demonstrates the clear link between wellbeing, adverse childhood experiences and poverty. The complex interaction of family, relationships, school, work, isolation and community is writ large. We can tell from her words that by the time Lyndsey started school, she was living in survival mode. The people around her responded to her distress and “acting out” by excluding her from school. We know that school exclusion increases a person’s sense of shame, alienation and their risk of suicide. These experiences impacted Lyndsey’s confidence, educational attainment, opportunities for further education and access to good work. This toxic combination of life experiences increases the likelihood of a young person being involved in crime and joining gangs. As a mother in a new community, Lyndsey again felt alienated and this had a further impact on her mental health. It has been well documented that good relationships and being involved with others is as protective to health as not smoking. Lyndsey’s alienation was exacerbated by a lack of access to transport, difficulties with managing the costs associated with her housing, and her and husband experiencing ‘in-work poverty’. Luckily, Lyndsey was able to receive support via Families First (not all FFP programmes have embedded psychology support). This service is something of which Wales should be proud. It provided practical help, alongside other organisations such as Home Start, to support Lyndsey’s family with food and clothing and helped her access the education she missed out on. Lyndsey’s local FFP offered relational support through the ‘Circle of Security’ parenting programme. This is helping her to address the intergenerational cycles of trauma, shame, alienation and adversity. Our hope is that the Welsh government keeps its commitment to prioritise mental health but does so in a way that joins up all the necessary parts needed for healthy communities and healthy social environments. No one should be expected to go it alone. Time to Tredegarise: PSC South Wales calls to Welsh Parliament In our letter to the Welsh government, as well as laying out some of the evidence for the connection between our societal and mental health (see above), we made the case for a mental health and poverty inclusive strategy. This is about far more than accessing the right ‘treatment’ at an early stage. It is about a fundamental shift in our recognition of what causes the distress that can lead to mental and physical health problems. You can read the letter here. We also said that we support the Bevan Foundation’s call for such a strategy to have clear lines of accountability across all the ministerial portfolios, rather than placing it at the feet of a new Minister for Poverty. Finally, to reduce the strain on our NHS budget, we called for genuine upstream prevention as well as early intervention. Within social security reform, we would welcome the strengthening and extension of universal services - namely our NHS and education systems. In 1948, NHS founder Aneurin Bevan said: “All I am doing is extending to the entire population of Britain the benefits we had in Tredegar for a generation or more. We are going to 'Tredegarise' you". Research from the Institute of Global Prosperity at University College London suggests that extending universal basic services could strengthen participation, build belonging, improve choice, common purpose and cohesion across society. We asked that the Welsh government commit to extending ‘Tredegarism’ a little further. AuthorWritten by Jen Daffin, a Clinical Psychologist in Training, Kiran Guye, a Clinical Psychologist in Training and Dr Sarah Brown, a Clinical Psychologist alongside Lyndsey Skinner, a parent.

1 Comment

|

AuthorPSC is a network of people interested in applying psychology to generate social and political action. You don't have to be a member of PSC to contribute to the blog Archives

February 2022

Categories

All

|

PSYCHOLOGISTS FOR SOCIAL CHANGE

- Home

- About

-

Groups

- Blog

-

Position statements

- UK >

-

Cymru / Wales

>

- Consultation Responses

- Housing Support Funding

- Connecting the Dots Report

- Chemical Imbalance Myth

- Review of use of dx PD

- UK Inhumane Removal Plans

- WG LGBT+actionplan

- Ty Coryton

- Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities: The Report

- ECT Review

- Black Lives Matter

- COVID 19 and Internet Access

- Save the T4CYP Programme

- Support the Mind over matter Report

- UN Report on Extreme Poverty in the UK Letter

- England >

- Ireland >

- Northern Ireland

- Scotland

-

Campaigns

- Join our mailing list

RSS Feed

RSS Feed