|

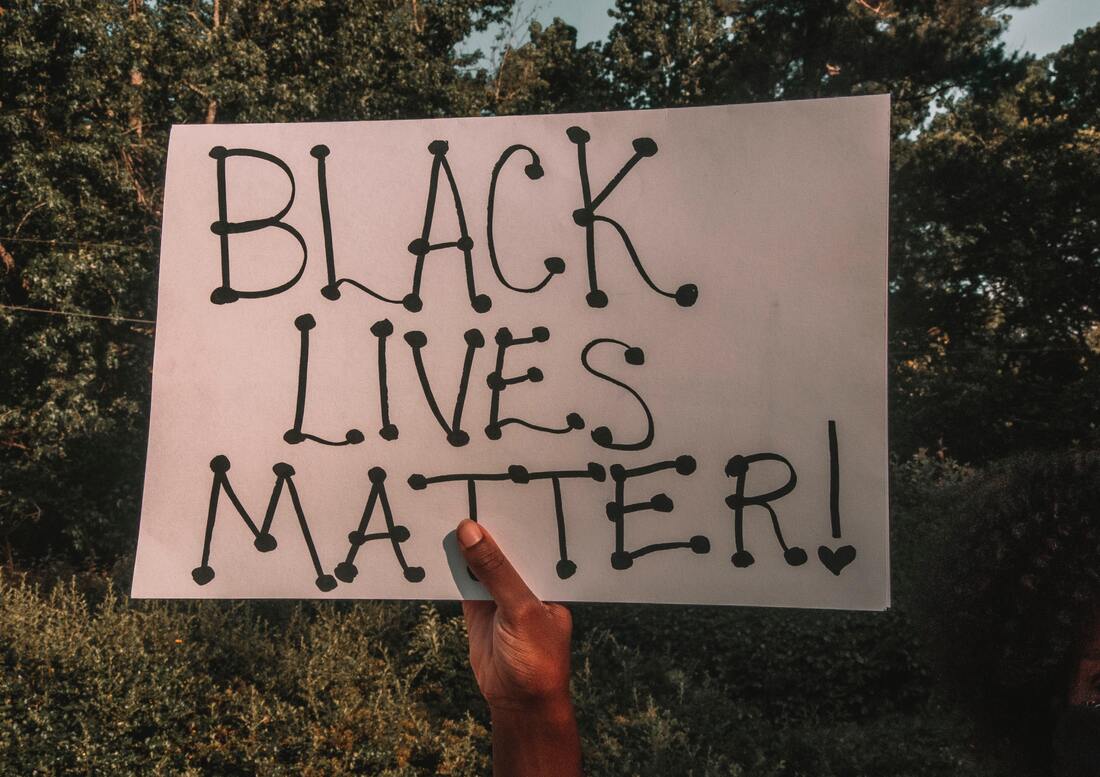

by Simon Goodman, De Montfort University, in collaboration with the BPS Social Psychology Section committee As the protests for the Black Lives Matter movement continue throughout the world, in the UK this has turned public attention to the country’s colonial and slave-owning past. This comes at a time when minority groups are being infected and dying at disproportionately higher levels from coronavirus and leading figures in the government appear to accept race science, eugenics, and with it the idea that there is a meaningful relationship between race and IQ. This post will show that the history of ‘race science’ is a history of racism, as it was developed to support and justify colonialism and has no scientific basis. Instead, psychologists, like everyone else, need to actively reject the notion of race as a meaningful concept, while also recognising that despite race not being real, racism very much is. While most psychologists tend to treat race as a common-sense idea (McCann-Mortimer, Augoustinos & LeCouteur, 2004), Montague (1964) showed the concept to be anything but scientific. He traced the use of the term race to Georges Le Clerc Buffon in 1749 in his six classifications of humans. Based on the religious thinking of the day, the races were deemed to have been created by God, but with ‘degradation’ from the original – and best – Caucasian race. While Caucasian may sound like a scientific term it actually comes from the Caucus mountains, on the border of Russia and Georgia, where it was then believed the Garden of Eden was, with Adam and Eve being the first Caucasians. This defining of race, however, did not exist in a value-free bubble; it coincided with the European colonisation of the rest of the world where it was convenient to deem the colonised people that were dominated and exploited as less advanced than the White colonisers. These ideas of ‘race’ spread, finding their way into eugenics and Nazi ideology with all the horrors that this brought. It is these very same ideas that underpin modern race science, so this is the legacy of any psychological work that addresses race in an uncritical way as a real and scientific category.

Despite this, Tate and Audette (2001) show how race continues to be wrongly treated as a natural variable, somehow distinct from political relations. This is particularly surprising as geneticists debunked the idea of race as natural even before the Second World War (Richards, 1997) and after the war the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, 1950) declared that the “biological fact of race and the myth of ‘race’ should be distinguished”. In 1972, Lewontin showed that the genetic difference within supposed racial groups was bigger than the differences between them, and more recently the Human Genome Project corroborated this stating that “the concept of race has no genetic or scientific basis”. This means that no psychologists or any other scientists should be using race as a real category. This is why Condor (1988) criticised social psychologists for using the term because to ‘take the existence and significance of ‘race’ categories for granted’ is to help maintain the idea that it is a meaningful concept, which can inadvertently reproduce racism. Instead, it is the different treatment of groups that leads to the differences between the groups, which is why Morgan (2020) concludes that the differences in coronavirus deaths in the UK are not due to racial differences but “are the result of structural racism”. This leaves us with a challenge: if race does not exist as a meaningful category, how do we oppose and challenge racism? Howarth and Hook (2005) offer some advice here: “What we do need to do is recognise the contradictory but necessary aims in presenting a critical analysis of racism … so while we have to acknowledge the continuing psychic hold and the materiality of racism … we as critical psychologists need to take up and challenge racialized practices”. Practically, I would therefore recommend that while psychologists continue their efforts to understand the causes of, and harm brought about by, racism that they must also never again treat race as real – this just serves to legitimise divisions. Attempts to look for racial differences must be understood as ideological and racist and any research that does this must be called out (like this). Instead, as Augoustinos and Every (2007) demonstrate, psychologists should focus on how the category of race is used “to justify and rationalise existing social inequities between groups."

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorPSC is a network of people interested in applying psychology to generate social and political action. You don't have to be a member of PSC to contribute to the blog Archives

February 2022

Categories

All

|

PSYCHOLOGISTS FOR SOCIAL CHANGE

- Home

- About

-

Groups

- Blog

-

Position statements

- UK >

-

Cymru / Wales

>

- Consultation Responses

- Housing Support Funding

- Connecting the Dots Report

- Chemical Imbalance Myth

- Review of use of dx PD

- UK Inhumane Removal Plans

- WG LGBT+actionplan

- Ty Coryton

- Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities: The Report

- ECT Review

- Black Lives Matter

- COVID 19 and Internet Access

- Save the T4CYP Programme

- Support the Mind over matter Report

- UN Report on Extreme Poverty in the UK Letter

- England >

- Ireland >

- Northern Ireland

- Scotland

-

Campaigns

- Join our mailing list

RSS Feed

RSS Feed